Carbon Capture Drillers Meet Demand from 270 Projects

Highlands Drilling shares how they’re navigating the uncertain frontier of carbon capture

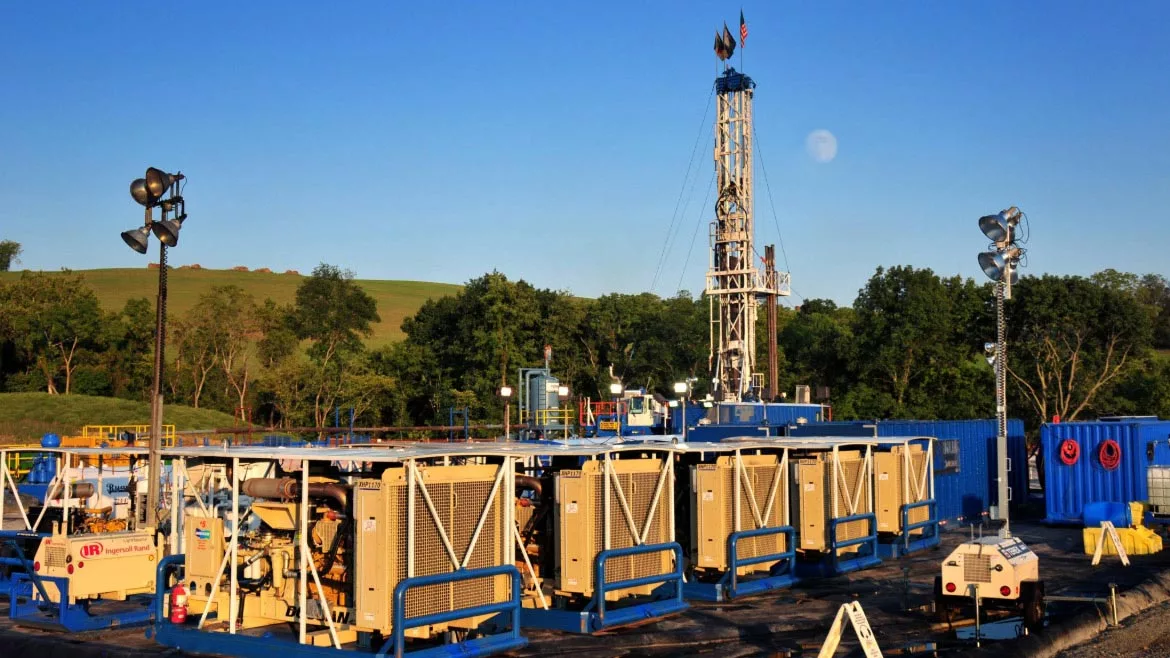

Highlands Drilling’s team prepares a rig in the Illinois Basin, where decades-old oilfields now anchor the future of carbon capture.

Image courtesy of Highlands Drilling

On a muggy morning in the Illinois Basin, Derek Haiden scans the horizon from the edge of a drilling site. For decades, these fields echoed with the machinery of oil and gas extraction. Today, the work is different, but the stakes are higher. Haiden, General Manager at Highlands Drilling, stands at the intersection of old-school energy know-how and the new frontier of carbon capture and storage (CCS).

Founded in 2006, Highlands Drilling built its reputation as a nimble independent contractor in the Appalachian Basin.

“We started with the industry’s only true ‘built for purpose’ drilling rigs,” Haiden recalled. “We’ve drilled everything from horizontal oil and gas, coal bed methane, vertical and top-hole wells, to intersecting in-situ and gas storage wells.” That breadth of experience, he said, is the company’s secret sauce as it pivots to CCS. “There’s nothing cookie-cutter about drilling CCS wells. Each one is basically a custom job.”

Highlands Drilling’s expansion into carbon capture didn’t happen by accident. As climate targets tightened and federal incentives, such as the Section 45Q tax credit established in 2008, gained momentum, the company recognized an opportunity.

“We’re dedicated to conducting drilling operations with the utmost consideration for the environment,” Haiden said. “Being at the forefront of carbon capture lets us take that commitment even further, aiming to contribute significantly to reducing greenhouse gas emissions.”

The technical shift has been profound. Traditional oil and gas wells are often drilled in known fields, using standardized methods honed over decades.

“CCS wells are fundamentally different,” Haiden said. “Permitting alone is a multi-year, intensive process. These Class VI sequestration wells go through far more scrutiny than oil and gas production wells. And once you start drilling, there’s no margin for error. You can’t just move the rig and try again.”

The wells are designed not to extract, but to inject and safely store CO₂ — requiring precision at every stage, from well design and drilling fluids to cementing and monitoring.

Highlands’ “built for purpose” drilling rigs – originally designed for Appalachian oil and gas – now adapted to CCS well requirements. Image courtesy of Highlands Drilling

A Federal Funding Whiplash

The urgency behind CCS has never been greater — or more complicated. In May, the U.S. Department of Energy abruptly terminated funding for 24 major energy projects, including several carbon capture initiatives, citing stalled progress and shifting priorities. The move sent shockwaves through the CCS sector, raising fears about the stability of federal support.

Jessie Stolark, Executive Director of the Carbon Capture Coalition, was blunt about the consequences.

“We were very disappointed,” she said. “A lot of those canceled projects were critical for deploying CCS in industries like natural gas, cement, and refining — areas where these technologies are essential for meeting emissions goals.”

Stolark stresses that while the cancellations don’t mean an end to CCS, they expose the fragility of the funding base for front-leading projects.

“We’re still seeing deployment, especially in lower-cost sectors like ethanol and natural gas processing, but there’s a real risk to the next generation of projects, especially in the power sector,” she said.

The U.S. has long been seen as the global leader in CCS, thanks to strong policy signals like the 45Q tax credit and extensive geological research by the Department of Energy and U.S. Geological Survey. But Stolark warns that other countries, notably Canada, are catching up fast.

“Canada has an industrial carbon tax and strong incentives for direct air capture. If U.S. policy becomes more uncertain, companies may look abroad for more stable ground,” she said.

A Highlands Drilling monitors CO₂ injection equipment, highlighting the custom engineering needed for every carbon storage well. Image courtesy of Highlands Drilling

The Technical Challenges Beneath the Surface

For Highlands Drilling, the transition to CCS has required importing lessons from years spent drilling solution mining and oil and gas wells — and innovating on the fly.

“Our experience across industries has taught us to use the right tools, techniques, and vendor partnerships for each job,” Haiden said. “In CCS, there’s usually little or no prior data about the geology, so we have to gather it as we drill. Data collection during the process is crucial to ensure well integrity and storage potential.”

Unlike oil and gas wells, which prioritize cost control and repeatability, CCS wells demand bespoke engineering.

“Reservoir pressures increase over time as you inject CO₂, so precision is critical to keep the well stable for years to come,” Haiden explained. “Everything from the drilling rig, support equipment, and bits, to the circulation methods and drilling fluids, is customized for each location. And after drilling, we’re still not done: deep and shallow monitoring wells are installed to watch for CO₂ migration throughout the life of the project.”

The importance of robust monitoring and rapid response was underscored last year when Archer Daniels Midland (ADM) detected a CO₂ leak at its CCS facility in Decatur, Illinois. The incident, while contained and managed under existing protocols, became a flashpoint in the broader debate over carbon storage safety.

Jessie Stolark of the Carbon Capture Coalition sees the ADM episode as proof of both the risks and the progress in the sector. “The key was that the leak was detected quickly — monitoring technology and regulatory oversight worked as intended, allowing ADM and regulators to respond appropriately,” she explained. “It’s a reminder that while no technology is risk-free, the systems in place can mitigate those risks and protect communities.”

For Highlands Drilling, incidents like ADM’s reinforce the necessity of exhaustive well design, continuous monitoring, and transparency with local stakeholders. “Casing and cementing programs are tailored to each site, in addition to deep and shallow monitoring wells being installed for exactly this reason,” Haiden said. “It’s about making sure that if something happens, it is detected immediately — and the community knows they are safe.”

The ADM event also had ripple effects in Washington, coloring the conversation around federal support for CCS. Lawmakers, wary of public backlash, are increasingly attuned to local concerns about safety — something industry leaders say must be addressed head-on if CCS is to scale.

“The regulatory response to the migration of CO2 outside the target formation at ADM showed the system’s strengths,” Stolark said, “but it also highlighted the need for continued investment in monitoring technology and public engagement. As CCS projects expand into new regions, building trust will be as important as drilling the wells themselves.”

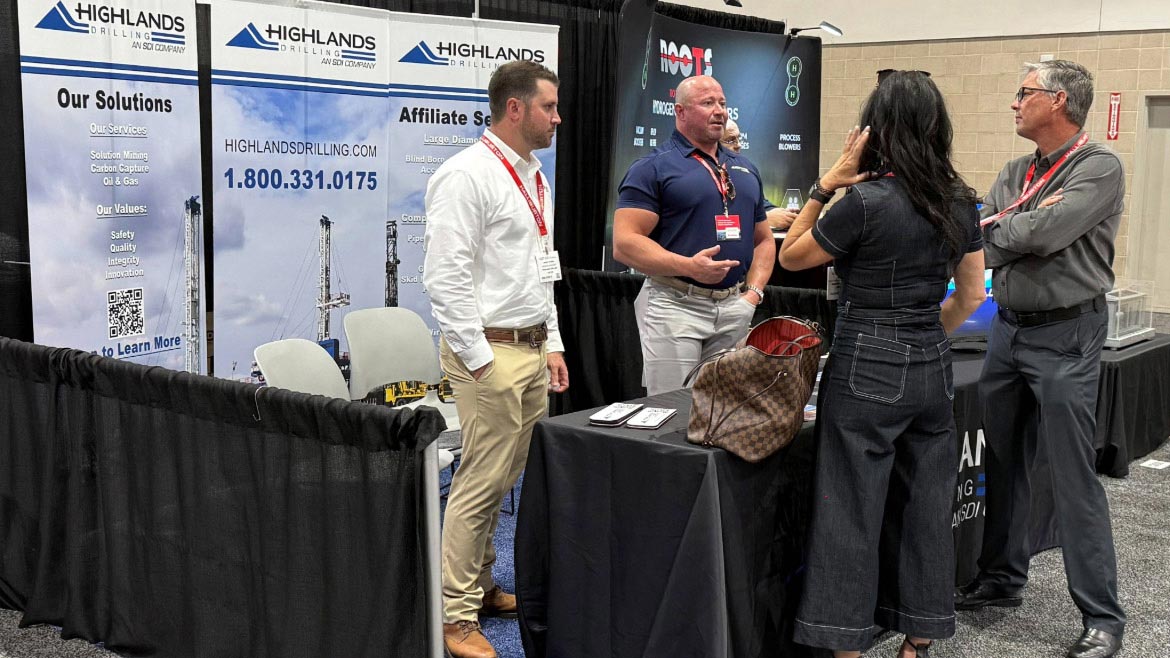

General Manager Derek Haiden and his team table booths and attend carbon capture trade shows like the Carbon Capture, Utilization and Storage conference in Houston in March. Image courtesy of Highlands Drilling

Navigating Regulation, Community, and Perception

The regulatory landscape for CCS is daunting. Class VI permits — required for CO₂ injection wells — take years to obtain, involving extensive environmental review and public comment.

“It’s much more stringent than anything in oil and gas,” Haiden said. “We collaborate closely with experts and research institutions to get it right, and we see that as an advantage. But it’s not easy.”

Community engagement is another key difference.

“In places like the Marcellus Shale, folks are used to seeing drilling rigs. Here in the Illinois Basin, some projects are inside city limits where a rig is an unusual sight,” Haiden noted. “We make it a priority to treat the roads, towns, and people with respect — as if it were our own community.”

The industry’s greatest challenge, Haiden believes, is public perception.

“There are a lot of misconceptions about drilling and its environmental impact,” he said. “What people don’t realize is that the U.S. has seen the largest reduction in carbon emissions in history over the last 20 years, directly related to the natural gas shale boom. Pair that with CCS, and the impact could be transformative. But we need to do a better job telling that story.”

At the heart of CCS’s future is the fate of the Section 45Q tax credit. The credit, which incentivizes CO₂ capture and storage, was preserved in recent budget negotiations, but is losing value due to inflation and policy delays. Transferability provisions — allowing project developers to sell tax credits — remain limited, creating uncertainty for investors. Congress is now considering enhancements, including inflation indexing and higher credit values, but the window for action is narrowing.

“The credit is in a good place for now,” Stolark said, “but if it doesn’t keep up with costs, projects could stall. The U.S. needs to maintain its edge, or risk losing ground to countries with stronger, more stable incentives.”

For Highlands Drilling and others working in the Illinois Basin, the path forward is both promising and fraught with uncertainty. More than 270 CCS projects are in development nationwide, spanning everything from ethanol refineries to heavy industry. But each project is a test of technical ingenuity, regulatory patience, and community trust.

Haiden remains undaunted. “We all want clean, reliable energy, and right now in 2025, the only way to get there is through smart drilling — whether that’s for natural gas, storage, or CCS. The technology works. The challenge is making it work at scale, and making sure people understand why it matters.”

Looking for a reprint of this article?

From high-res PDFs to custom plaques, order your copy today!