Colorado River Basin in Crisis

Shrinking Snowpack and Reservoirs Threaten Water Supply

Image Credit: John Oldani

As of mid-May 2025, a water crisis is tightening its grip on the Colorado River Basin, raising serious concerns for millions of residents, farmers, and ecosystems across the American West.

The snowpack—the critical natural reservoir that feeds the river each spring—is alarmingly low, and the region’s most vital reservoirs are continuing to shrink. Scientists, officials, and water managers are sounding the alarm: if conditions don’t improve soon, tough decisions and even tougher consequences could follow.

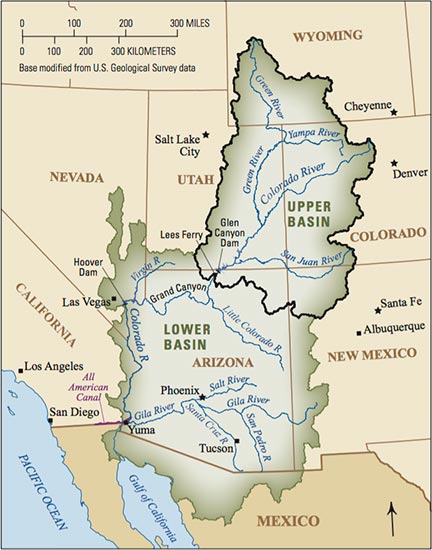

Facts about the Basin: The Colorado River Basin stretches approximately 1,450 miles (2,334 km) from the Rocky Mountains of Colorado to the Gulf of California in Mexico.

It spans across seven U.S. states—Colorado, Wyoming, Utah, New Mexico, Nevada, Arizona, and California—and two Mexican states: Sonora and Baja California.

- It provides water to around 40 million people in the U.S. and Mexico. This includes major cities like Los Angeles, Las Vegas, Phoenix, Denver, and San Diego, along with agriculture, tribal nations, and ecosystems across the Southwest.

Map courtesy of USGS.gov

Snowpack Shortfall

At the heart of this unfolding crisis is the Upper Colorado River Basin’s depleted snowpack, currently holding just 62% of its typical water content for this time of year. That number isn’t just below average—it’s dangerously low. Snowpack acts as the river’s lifeline, slowly melting and supplying water through spring and summer. But this year, forecasts predict the runoff into Lake Powell during the crucial April-to-July period will reach only 55% of the 30-year average.

“It’s looking like a pretty poor water supply and spring runoff season,” said Cody Moser, a hydrologist with the Colorado River Basin Forecast Center.

The problem doesn’t stop with the snow. Parched soil across the region, baked dry from ongoing drought, is soaking up much of the meltwater before it ever reaches streams or reservoirs. It’s a one-two punch: less snow, and less water actually making it to where it’s needed.

Reservoirs on the Decline

Lake Powell, one of the country’s most important water storage facilities, is bearing the brunt. Since the start of Water Year 2025, the reservoir has lost about 1.5 million acre-feet of water. Outflows continue to exceed inflows, and current operations fall under the Mid-Elevation Release Tier, requiring an annual release of 7.48 million acre-feet. As stated by the Bureau of Reclamation, “Lake Powell is projected to release 7.48 million acre-feet of water in 2025.”

However, if projections show Lake Powell’s elevation falling below 3,500 feet, those releases may be slashed to 6.0 million acre-feet. That’s the threshold needed to maintain hydropower generation, a critical energy source for millions. The Bureau of Reclamation also confirmed, “Lake Powell will operate in a Mid-Elevation Release Tier in water year 2025 and Lake Mead will operate in a Level 1 Shortage Condition with required shortages by Arizona and Nevada.”

Downstream, Lake Mead isn’t faring much better. Despite some conservation gains, the reservoir is at just 33% of its full capacity as of May 2025—a level that leaves little room for error. “It’s going to be a painful summer, watching the levels go down,” said Kyle Roerink, executive director of the Great Basin Water Network. “We’re getting to those dangerous levels we saw a few years ago.”

A Crisis Years in the Making

This water emergency didn’t arrive overnight. In August 2022, as worsening drought conditions devastated western communities, the U.S. Department of the Interior announced urgent measures to protect the long-term sustainability of the Colorado River System. Prolonged drought and low runoff—both intensified by climate change—had already driven Lakes Powell and Mead to historic lows. The Bureau of Reclamation’s 24-Month Study at the time set the stage for tough decisions about operations in 2023, emphasizing that additional action would be necessary to prevent the collapse of the system.

Over the last two decades, federal leaders and basin states worked on a series of drought response efforts. But as water levels kept dropping, urgency replaced caution. That urgency has only intensified in 2025.

Today, water managers are walking a tightrope. With climate uncertainty looming large, officials are adjusting water release plans and pressing users to cut back. Every drop counts. “We have to acknowledge that cuts [in water use] are probable, possible and likely,” said Water Education Colorado, summarizing the sobering outlook.

These aren’t just abstract numbers. They impact real lives—families relying on tap water, farmers facing reduced irrigation, ecosystems struggling to survive. The situation is changing quickly, and experts agree: continued monitoring, adaptability, and community-wide conservation will be essential to weather the drought.

Federal officials echo the need for collective action. “As the West continues to face drought conditions, now is the time for more investment, innovation and collaboration for urgent and essential progress across the Colorado River Basin,” stated the U.S. Department of the Interior.

As the Southwest braces for a long, dry summer, one thing is clear: the Colorado River is in trouble. And if we don’t act decisively now, the consequences could ripple far beyond the riverbanks.

Looking for a reprint of this article?

From high-res PDFs to custom plaques, order your copy today!