University of Texas Initiative Goes Deeper on Geothermal

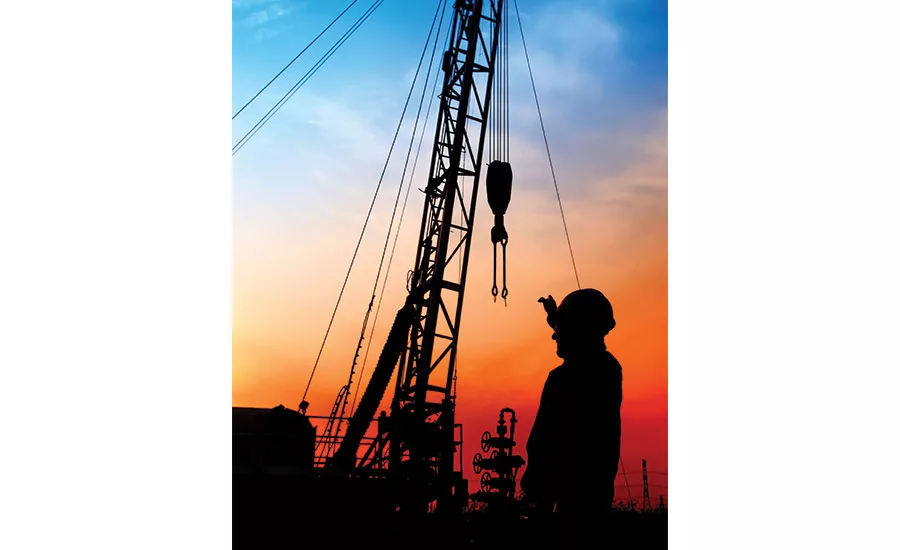

Young workers in the oil and gas space can now consider a future where their skills go to work in on CO2-free jobs.

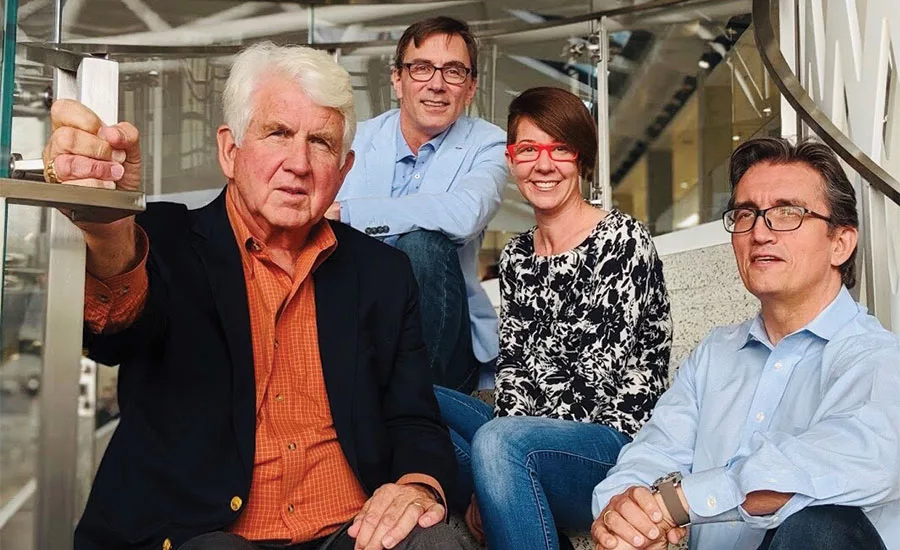

The GEO leadership team, from left, Bob Metcalfe, Ken Wisian, Jamie Beard and Eric van Oort.

Source: University of Texas

Imagine a “green” energy future. Now imagine an army of drillers from the oil and gas industry working hard to make that future a reality.

That’s the concept driving the new Geothermal Entrepreneurship Organization (GEO) in the Cockrell School of Engineering at The University of Texas at Austin. GEO started last year with a $1 million grant from the U.S. Department of Energy. It aims to be an “integrator” for deep, high-pressure geothermal systems in Texas and beyond. The group seeks to foster the development and commercialization of technologies that effectively and inexpensively drill to depths up to 30,000 feet and in temperatures over 350 degrees. Meeting that goal means the feasibility of powering grids anywhere in the world through geothermal energy, not just in hot spots where requisite temperatures sit relatively close to the surface.

To find out more, we spoke with Jamie Beard, executive director of GEO, and Eric van Oort, a professor in the Hildebrand Department of Petroleum and Geosystems Engineering and a co-investigator for the group. Our conversation here has been edited for space and clarity.

Q. First off, briefly describe what the new Geothermal Entrepreneurship Organization (GEO) initiative is. Who is involved and what are the goals?

JB: The purpose of GEO is really to build an innovation ecosystem for geothermal, not only at UT-Austin, but in Texas generally. We’re really trying to wrap in the oil and gas industry, because they’re so perfectly positioned to help with the technological problem set associated with deep, supercritical geothermal. It was a $1 million dollar grant that the Department of Energy gave us to build the structure for a lasting ecosystem. Essentially, what that means is to build a lasting institute at the University of Texas at Austin that’s going to pursue interdisciplinary collaborations and research for geothermal-related problems, leveraging industry partnerships that have been a legacy at UT, that already exist, with the oil and gas industry.

There’s an important component actually reflected in the name of GEO, which is filling a technology gap. When you have a research university like UT pursuing research and even technology development, oftentimes the result is a little too early for the industry to use in any way. ... You have a proven concept or a very early prototype, but it’s not something that the industry can easily test or deploy in the field because it’s too early in technology readiness. One of the angles of GEO is to assure that the developments we are producing through our inquiries are pushed forward to a technology readiness level sufficient for the industry to engage — essentially doing a start-up exercise. There are some robust startup and entrepreneurial ecosystems at UT, but also in Austin, that stand ready to help with that, right? So if we have something that’s promising, we can actually build a team, crank out a startup company and that startup company can then advance the prototype to a level that the industry can more easily engage with. The commercialization component is kind of a second phase of GEO to help make sure that what we’re cranking out is actually relevant.

Q. Why isn’t this type of geothermal already widespread in the United States?

JB: The concept that GEO is pursuing is actually not being pursued anywhere yet, because it’s a brand new concept. Eric can dive into the technical aspects of that. But what we’re interested in doing is closed-loop systems — really deep, high-pressure, really hot geothermal where you can drill for it literally anywhere in the world. What we’re hoping to enable is geothermal baseload, geothermal everywhere, not just geothermal as it is currently, which is available in very specific and limited geographical areas of the world. Eric is an expert at the technical details of that, but this is essentially leveraging legacy high-temperature and pressure knowledge, best policies and technologies from the oil and gas industry to enable something entirely new. It’s a new paradigm, the future of geothermal energy.

EV: It is a good question. I took UT out to a consortium called RAPID, which has 20 companies supporting it, and I actually talked about GEO to those companies last week. The first response when I showed them the deep closed-loop concept that Jamie talked about, they said, “Well, why hasn’t oil and gas done that already?” The answer to that is, yeah the geothermal world and the oil and gas world have been separated for a long, long time and never the twain shall meet, right? But the oil and gas world has been drilling deep high-pressure, high-temperature wells for many years now and has a lot of expertise. Certainly, the people in the room last week said they were excited by this concept and they thought it was doable with the technology and the know-how that we’ve gained in oil and gas.

Q. From a technical standpoint, I’m sure plenty of similarities exist between oil and gas drilling and this type of deep geothermal energy. How are they different?

EV: They actually are not. They aren’t as far as the technical challenges go. Now, there are quite a few challenges on the legal side, the asset side, and Jamie can speak to that. Who owns the heat is the really important question. But from a technical standpoint, drilling high-temperature, high-pressure wells — the technical challenges are very similar. You’re talking about materials that can stand up to high temperatures, products that can stand up to temperatures. You need to have fluids, cemented casing that can deal with the challenging conditions, and that is not different. Technically, that’s the same challenge. But I’ll let Jamie talk about the other challenges, because there are of course some fundamental differences.

JB: The concept is so blue sky right now, that it raises all kinds of interesting inquiries, which makes it interesting for a major interdisciplinary effort. From what I can tell engaging with folks about the concept in the oil and gas industry, the timing has just not been right. With the cheap gas, there’s just not been a focus on what’s next for the industry post-fossil fuels. So they are looking at solar and wind. But it’s just geothermal, for some reason — it seems completely obvious that this could be such a beautiful pivot for the oil and gas industry, right? To leverage everything they already do and know, all of their workforce, all of their IT, all of the methodologies that have been developed over the last 100 years to drill for clean energy. It’s beautiful, but for some reason this is not been obvious to the industry. But, all the way up the chain to the executive vice presidents of major, multinational operators, when you present the concept to them, it’s like, “Wow, that’s really interesting.” The reaction isn’t, “Oh, we thought of that, and we decided not to do it.” The reaction is, “Eureka! That’s really interesting.” There’s not a clear answer to why it hasn’t happened, except the timing perhaps hasn’t been right. There hasn’t been enough discussion about climate and post-fossil fuels, etc. I think now the timing is precisely right.

When it comes to the non-technical parts of the concept, those actually might be the most difficult when it comes to making this really happen. Politically, the concept is naturally bipartisan, but it does set up the potential to have a very polarizing reaction to it. We’re trying to work hard to make that not happen, right? We don’t want this to become a Republican or a Democrat concept. We want it to be an everybody-at-the-table concept. Politically, there could be challenges. In the U.S., policy incentives are very biased toward traditional, intermittent renewables — so solar and wind. The geothermal industry has largely been left out of that. It’s kind of this forgotten renewable that has flown under the radar that needs a very public push to say, “Hey, not only is this gigantic and ubiquitous and can baseload and leverages an existing robust industry, but it’s CO2 free, right?” It’s also really quickly deployable. We could do this in a decade. It’s a really compelling concept. So it needs some policy instruments.

The legal stuff is also interesting. If this were to happen in the next decade where the oil and gas industry decides, “Hey, cool, we’re just going to make heat our asset,” there’s this just blue sky territory where it’s like “Wow, will the last 100 years of jurisprudence that have settled oil and gas leasing ... get completely thrown on its head?” We’re talking about resources that are much deeper below any oil and gas leasing that occurs now. It’s a resource that emanates from a place in the earth that no one owns. It’s really interesting [to think about] who owns heat. That’s something that’s going to have to be quickly thought about. It will essentially be a free-for-all at first. It’s going to be one of these new territories, kind of like fracking, where it was just like, “Hey, let’s wildcat this and do it and let things fall where they fall later.”

Q. Texas, in particular, has many existing oil wells. Can those be repurposed for this type of geothermal, or does it require new wells?

EV: Possibly. We’d have to see. Maybe for exploration purposes, they could be used. Existing wells could be deepened. The question is, do you have the hole size, do you have the casing program available to get to the depth that you need to go? For real production wells, they have to be custom designed particularly for the thermal loads. The casing design is a discipline all by itself, and load resistance is really, really important. So you have to look at all the potential load cases, which of course in these ultra-high-pressure, high-temperature wells are pretty stringent.

Q. For oil and gas companies, what incentive is there to put resources into geothermal instead? Isn’t a geothermal loop a longer-horizon, maybe 30- or 40-year asset? Wouldn’t drilling geothermal systems involve drilling and supporting fewer wells?

JB: We’re not quite sure. There needs to be work done and modeling done to determine the length of the asset. It’s one of those unknowns for this type of project, but yes, 30 to 40 years is the estimated minimum. But these are largely educated guesses at this point because it’s not been done. ... It’s a question that is kind of just answering itself in terms of engagement, because they are interested. ... It’s been my experience so far that the more the concept has been in the media, the more interest in terms of double-digit thousands of people engaging on LinkedIn posts about the concept. This is from Houston in the oil and gas industry all the way up and down the chain from C-level folks to exploration geologists saying, “Wow, this is so cool. I really want to work on that.”

Even in a grassroots way, this is gaining traction in some of the larger operators, which is really cool to see. There are a lot of things that go into that. I think some of the younger folks working in petroleum engineering are really interested in seeing what the picture of their careers will be 30, 40 years down the road. This offers something exciting and promising, right? It’s like a new frontier that’s clean, that leverages their schooling and everything they know. There’s just an energy behind this that is self-sustaining, and it’s great.

Why they would pivot, why they would engage — I think that’s a question of business strategy. The operators are really busy right now, (1) becoming power producers and (2) acquiring technologies and companies that have literally nothing to do with anything they know currently. They’re out buying wind companies and solar farms. It’s a good strategy to diversify, but this is square one. ... Why not develop the clean energy future that leverages everything you do, know, own and all of your workforce to do the same thing? It’s a concept that’s resonating deeply because of that. They’re doing this anyway. They’re looking to clean energy, they’re diversifying, they’re becoming power producers. This just really hits the nail on the head when it comes to business strategy and looking at the future.

Q. You’ve said your goal is to make geothermal energy a ubiquitous utility within 10 years. What roadblocks do you see to that happening?

EV: There are some major technical issues to overcome on my side. It’s primarily on the well construction side, the drilling and well completion side. We’re going into areas where we have not not been before. It’s just outside the operating range of where we have been drilling. If you look at high-pressure, high-temperature wells that have been drilled by the gas industry, we’re getting right outside the envelope. But we do need the development of some new technologies. We need bits that can stand up to the high temperatures and the high rock strengths. You need alloys and tubulars that can handle those connections. You need fluids that you can circulate in those wells. You need cement and casing that can stand up to it. Downhole electronics and maintaining them is a challenge. There is the challenge of directional drilling at large depth.

So what we’ve done is a thorough mapping out the technical challenges, the individual elements that need to be covered. What we would like to do is work with industry partners and, of course, funding organizations to fund R&D into targeted development of those technologies that we need, and then act as the integrator putting it all together.

The problem that the geothermal industry suffers from right now is that there are good bits and pieces going on everywhere — new technologies, new ways of drilling, some interesting things about directional drilling and so on — but nobody acts as an integrator. I think that’s an important role that we can play. Also, coming from the academic side, we have a good total overview of the problem, of all the elements that need to fall in place, basically all the pieces of the puzzle. So we can start putting those together with individual entities developing the various pieces.

Q. What can my readers do to help?

JB: Well sure. I mean, I think that from the GEO perspective, any type of idea about collaboration is welcome whether that’s, “Hey, I have a really interesting invention or technology that could contribute,” or “Hey, I work at a company that I think would be really excited about this concept. What can I do to get them engaged?” We welcome all types of engagement and interest. ... It doesn’t matter where you are in the world, if you’ve got something that’s relevant and interesting — ultra-high temperature anything, SO sensors, electronics, energy storage devices, you name it — we want to hear about it because we need everybody at the table that’s got relevant expertise and technologies to make this happen.

Looking for a reprint of this article?

From high-res PDFs to custom plaques, order your copy today!