An Update on Groundwater Management Regulations

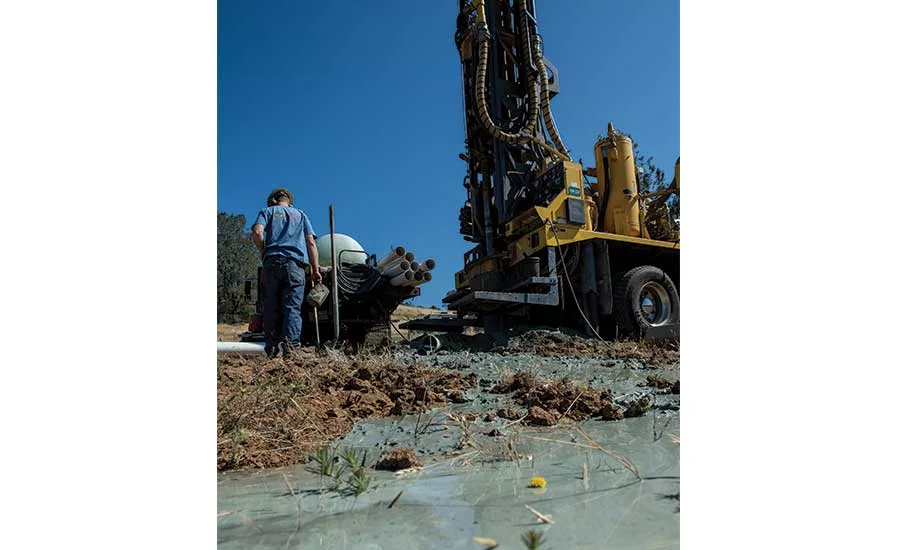

Since water well drillers depend on groundwater to make a living, groundwater management is an important topic for them to keep up with. Source: The California Department of Water Resources photos

Water well contractors are encouraged to take an active role in state and local groundwater management efforts to ensure their interests are considered, as well as those of the well owners they serve. Source: The California Department of Water Resources

Groundwater is a vital water supply resource in California and Texas, and both states are taking a local level approach to groundwater management. Source: The California Department of Water Resources

U.S. Geological Survey (USGS) hydrologist Jason Ramage collects a groundwater-level measurement using a steel tape in Freeport, Texas. Source: Sachin Shah, USGS

Groundwater is a fundamental resource for water well drillers; without it, they lose their livelihood. Well-intended rules surrounding groundwater sustainability are on the rise across the country, so what do they look like and how might they impact drillers? To find answers to these questions, National Driller recently interviewed water management leaders from California and Texas, two of the nation’s largest states with some of the most diverse climates. It isn’t uncommon for the rest of the nation to follow their lead and, when it comes to groundwater, both states are placing most of the power in the hands of localities.

Mike Meyer, incoming president of the California Groundwater Association (CGA), grew up in the drilling industry and has more than 15 years of well drilling experience across the State of California. He says groundwater management ranks among CGA’s top issues, and that the drilling community should recognize the importance of groundwater sustainability. “Water well professionals should be concerned about the quality and quantity of groundwater basins by their customers. Having it managed is the first step in knowing there’s going to be that quantity and quality available for future generations,” Meyer says.

Local Approaches to Groundwater Sustainability

Groundwater is a critical resource in the state of California, according to the California Department of Water Resources (DWR). It provides approximately 30 to 46 percent of the state’s total water supply. Some communities in California are 100-percent reliant on groundwater. Recognizing the urgent need for sustainable groundwater management, Gov. Edmund G. Brown Jr. signed the Sustainable Groundwater Management Act (SGMA) in September 2014.

Lauren Bisnett, DWR information officer, says SGMA sets the stage for local agencies, the DWR and the State Water Resources Control Board to meet new goals for groundwater basins. “Really, the pillar of the law is that locals know their groundwater resources best, and they’ll have some of the best insights and innovations on how to make them sustainable. So the act is really about empowering local management,” Bisnett says.

SGMA is characterized as a framework for groundwater management that offers minimum standards. Bisnett says it is important to understand that there is no one list of rules and that each groundwater sustainability agency (GSA) formed as a result of SGMA will determine its own unique management policies applicable to the local basin. Powers for GSAs described by SGMA include: the ability to charge fees, conduct investigations, register wells, require reporting, etc.

Important drivers of locally-empowered groundwater management in California are the state’s diverse climate, hydrology and geology. Swift changes from drought to flood are relatively common historically. In addition, every groundwater basin is different; at any point in time, some may face scarcity while others face a surplus. “It’s essential that local and regional agencies exercise leadership to implement locally-appropriate solutions,” Bisnett says. “Then, in terms of enforcement, the State Water Resources Control Board, under the EPA, is really the backstop. The state agency would step in only when local agencies are unwilling or unable to manage their groundwater basins sustainably.”

While California’s climate varies vastly from north to south, Larry French points out that Texas’ climate does so from east to west. Director of groundwater for the Texas Water Development Board (TWDB), French says groundwater is an important topic in his state. Groundwater provides approximately 60 percent of the 16.1 million acre-feet of water used in Texas. He views California and Texas groundwater management philosophies as quite similar. “It basically ends up being the same kind of end point: What do you want your aquifer to look like in the future and what actions are you going to take as a district, as you’re responsible for the management of the resource?” he says.

French explains that groundwater management in Texas is handled locally, through political units called groundwater conservation districts (GCD). There are 98 of them across the state, created by either the Texas legislature or the Texas Commission on Environmental Quality through a local petition process. GCDs are covered under the Texas Constitution, Article III, Section 52, or Article XVI, Section 59, and have the authority to regulate the spacing of water wells, production from water wells or both. The first GCD in Texas, the High Plains Underground Water Conservation District (UWCD), was created in 1951. Approximately 70 percent of Texas and 72 percent of its aquifers are covered by a GCD.

“Groundwater in Texas, like in California, is a private property right. So that’s why it’s done on a local level, essentially through local control,” French says.

Another important characteristic of groundwater management in Texas is collaboration between local management districts. Prior to 2005, groundwater availability in Texas was determined by planning groups with input from GCDs. In 2005, the Texas legislature passed House Bill 1763, which placed that responsibility in the hands of GCDs. It requires that districts within groundwater management areas work together to develop “desired future conditions” for given aquifers in their area. “The desired future condition for an aquifer is a statement that answers the question: ‘What do you want your aquifer to look like in the future?’ ” French explains. “That, in a state as large as Texas and with a variety of aquifers, can be expressed in a whole bunch of different ways.”

French says the most common way for districts to express their desired future condition is by determining how much lowering of water levels they can tolerate over a certain period of time. He says a number of factors have to be considered including: aquifer conditions (i.e. permeability, thickness, formation geometry, etc.), how groundwater is used in their area, plans for future use of the aquifer, interaction with surface water, private property rights, socioeconomic conditions, etc.

“I think the legislature recognizes it’s a good thing to basically have the whole process grounded in science and recognizes these aquifers behave in a way that one district’s actions can affect groundwater in an adjacent district, and so forth,” French says.

Drilling Industry Impact

From a macro point of view, Meyer says comprehensive groundwater management planning is a good idea. As an association, he says CGA supports groundwater protection and that with the recent drought at the forefront of Californians’ minds, SGMA didn’t face a lot of backlash. Meyer says the implementation of SGMA moving forward will determine impact on the water well drilling community and that they are still waiting to see how it all plays out.

One important challenge Meyer has been informed about is tied to local involvement. “We’ve had several members who’ve wanted to be part of groundwater agencies for their local basin and it’s been a little bit of a battle to actually get on and be part of the decision-making process,” he says.

In areas over basins with lower-than-ideal groundwater levels, Meyer imagines new well business will slow down. With that, he can see well service activity and well rehab taking priority, should it become harder to obtain new well permits. But he highlights that is only speculation. “It might be bad for business in the short run, but dividing up a scarce resource so that it can be used properly might turn out to be better for business in the long run,” Meyer says.

In the meantime, he encourages water well drillers to get involved with GSAs in the areas they serve. In addition, he urges participation in the state association, which can help keep them up to speed on new legislation. CGA and associations like it across the nation play an important part in connecting the groundwater industry with members of Congress. Meyer says to attend the “Day at the Capitol,” meet with representatives locally, and express questions and concerns about the impact of groundwater management regulations on water well businesses.

Both Bisnett and French echo Meyer’s sentiments about involvement and engagement. They welcome drillers in their states to use their agencies’ resources, attend planning meetings and take part in the public processes that inform new rules. French notes that the drilling records contractors already provide per project contribute to the scientific databases used by decision makers in Texas.

With so much variation across each state, Bisnett says drillers should not only understand the state-level groundwater management framework, but the unique local rules for the regions they serve. Drillers who cover the entirety of their states, or more than one state, will have more to keep up with and will need to adjust certain business approaches based on the location of a given job.

So, are groundwater management approaches like those in California and Texas bad for water well drilling business? Bisnett says not at all. “To the contrary, I really think it means good things for the community. The whole point of groundwater management is to preserve groundwater. So sustainable groundwater management and the act is going to support and sustain those California businesses and industries that help fuel our economies by ensuring that those water supplies are available now and for generations to come.”

Groundwater Management Progress

Two years after the launch of SGMA, Bisnett says the current state of California groundwater resources can be described as varied. On a positive note, especially after a long period of drought, she says water year 2017 — Oct. 1, 2016 through Sept. 30, 2017 — started with one of the wettest starts on record. “So we came right out of a drought into the midst of heavy precipitation, really solid snow pack, which is all really positive,” she says.

Based on groundwater level readings from spring 2017, she says impacts differ across the state. Water levels in shallow basins may show quick improvement, while deeper, more severely depleted groundwater basins — like those in critical overdraft in the Central Valley — may take years to recharge. Comparing spring 2017 data to spring 2011 data, Bisnett says approximately 47 percent of the monitoring wells in California showed less than 5 feet of change in either direction. Approximately 16 percent of the wells showed significantly lower groundwater elevations compared to 2011. “So in short … this last year has mostly recovered from last year. They have not yet recovered to pre-drought conditions in much of the state,” Bisnett explains.

Down in Texas, French says overall groundwater conditions can be summed up in the same way as California: varied. There are portions of the state with significantly depleted aquifers due to high groundwater pumping activity. There are other areas where quite the opposite is true. Some of the aquifers recharge quickly, but French says most of them do slowly, with the recharge rate slower than the withdrawal rate.

Groundwater sustainability is a broad issue with a variety of stakeholders and factors to consider in terms of management approach. Recent initiatives aimed at conserving the resource should not be expected to foster marked results overnight.

“Getting to sustainable management is going to take decades,” Bisnett says. “It’s not going to be easy, but we’re already seeing that local managers have stepped up to the challenge. … So while there are still challenges ahead, notably the development and implementation of these local groundwater sustainability plans, things are off to a really good start.”

For more information on groundwater management in California and Texas, go to www.water.ca.gov/groundwater and www.twdb.texas.gov/groundwater.

Looking for a reprint of this article?

From high-res PDFs to custom plaques, order your copy today!