Mentoring, Coaching Tips for New Drillers

Building a team for the jobsite (and beyond) takes trust. Having processes for tasks in place, and accountability for when processes are not followed, builds that trust.

Source: Brock Yordy

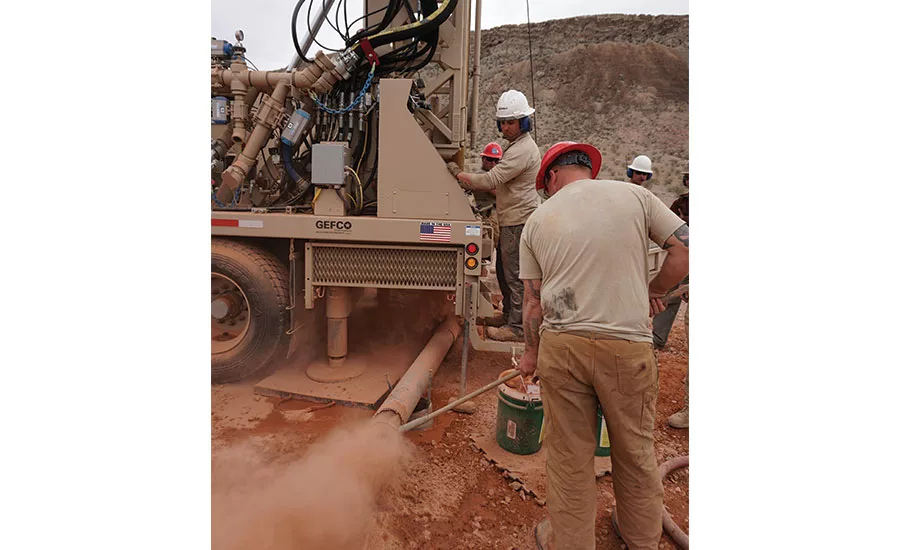

Training on the jobsite can often be a trial-by-fire, but ideally it would start under less deadline-intensive circumstances.

Source: Brock Yordy photos

Today’s young drillers and helpers will take on a worsening global water crisis. It’s the job of drilling veterans to coach and mentor them so they are up to the challenge.

When issues arise on the jobsite, good mentors quickly overcome ego and shift from wanting to blame people to wanting to solve the problem and share the lesson.

Source: Brock Yordy

Drilling is a skill set that continues to develop with each project completion. There are days when the mast is lowered, jacks are raised and we all high five as we celebrate another completed water well. Other days we climb into the truck at 9:30 p.m., exhausted and covered in mud as we realize that we missed dinner with the family by three hours.

Regardless of how the day ends, we take ownership of the success or failure. It is ingrained on every great driller that project success depends 100 percent on being at the controls or in control. This foundational belief in the drilling industry now holds us back from developing and leading the next generation of great drillers.

Article Index:

Finding Ideal Candidates

In the ideal situation, driller development starts when a student ready to learn seeks out formal training. However, drilling conditions are never ideal and often driller development starts unwillingly, with an individual thrown onto the platform and expected to perform. This trial-by-fire development process has created good and bad drillers. Knowing how this often happens in the field, my ideal candidate for driller development is just as excited to learn new skills as he or she is to unlearn bad habits.

A willingness to recognize that there could be a better way to get the job done creates a strong foundation for driller development. A new driller with the passion to learn new process and methods will continue to grow, with or without a great driller coach. The question then becomes, how long it will take that driller to develop on their own versus with a great mentor? Alternatively, how does the independent development process affect your company’s bottom line?

A Great Mentor or Coach

The best mentors and coaches — the ones who have had an impact on my life and career — have had an endless passion for learning. Excellent mentors teach students everything they know so that they can continue to develop their own craft. Great mentors include students in critical discussions. In my case, they had the same drive I did to question process improvement, but they took it a step further by creating a mutual exchange of knowledge and troubleshooting. A great mentor can coach and learn from their peer at the same time, creating a bond built on expertise and trust.

Choosing a mentor for a young or new driller can be incredibly difficult. The common theme is to take the best driller in a company and have them teach that developing driller. The problem with choosing your best driller as a coach is the balance between successful project execution and time to train. Consider the pressure and expectations your most productive driller is under. It is unrealistic to believe they have time to perform and develop new talent. Therefore, a company must choose coaching projects wisely so as not to sacrifice project execution over crew development. Management must recognize that the best driller and a great teacher do not have to be the same person. Many great drillers do not want to be teachers and that is okay.

A great mentor can coach and learn from their peer at the same time, creating a bond built on expertise and trust.

My first mentor beyond my father was not a driller, but a driller’s helper. My uncle Karl worked part-time for my family’s drilling company and was a full-time farmer. He coached with patience, humor and indirect refocusing. Karl would focus me back on a task by asking me to explain the next steps in the process. He increased my project success by inadvertently slowing me down and mitigating risk. No matter what bad situation could happen, he would find a way to make it a teachable moment that felt like a peer-to-peer discussion.

His mentoring style was so subtle and simplistic that I was unaware of my growth in confidence as a young driller. The idea to develop a young driller with an experienced helper might appear unconventional, but to experienced drill trainers it is brilliant. My colleague and National Driller columnist Dave Bowers teaches that the best driller helpers foster an environment where the driller can entirely focus on the task at hand. My father trusted Karl to support my growth and to mentor me, although he had never stepped onto the drilling platform. The growth of a driller is in the team built around them.

Building a Team for Growth

Building a team starts with creating trust among all members, from the office to the field. Trust comes from clearly defined job processes that allow for accountability. To overcome the unknown aspects of drilling, we must create procedures for all known elements of the job, including health, safety and environmental risks, and everyday tasks like mobilization and demobilization. If our teams know and understand these aspects, they can eliminate possibilities for failure. Defining processes promotes growth by building confidence within the organization and preparing crews for success. The goal is to set drillers and teams up for safe and efficient project completion. A company must trust their people and process.

Creating Trust

Over the past year, I worked on a drill team with two men, both of whom were under the age of 30. Bryan and Tyler are two of the best drillers that I ever worked with. However, we did not start as a competent, functional team; it took mutual sharing of processes and expectations. When I started with them in September 2018, they knew that I coach and train drill teams throughout the world. Bryan and Tyler were developing into good drillers without any coaching or reading. They had processes and methods in place that worked for them, and were successful on many geothermal projects throughout the Midwest. It was humbling to me when I realized that coaching men and women that want my help is different from a drill team assigned to work with me.

Our first project together was a high-profile job with a tight deadline and many risks in successful execution. We compounded the stakes by purchasing a new V-140 Versa-Drill and solids control system. As a team, we discussed expectations for the job and immediately went to work. When the project did not execute precisely as planned, my first tactic was to reaffirm the plan with the team to ensure we maintained schedule.

As the job got back on track, I left to do a site assessment. I wasn’t gone 20 minutes when the guys called to explain that they encountered downhole complications and the rods were stuck. I instantly started channeling my inner driller and thought, if I had been on the platform the situation would not have happened. I created a culture of blame that in turn made Bryan and Tyler defensive. Nothing productive came from me, believing that I could have prevented the unknown.

Once I realized my error, I went back to channeling my inner mentor, and we discussed the downhole issues and what it would take to overcome them. The hardest thing to overcome on a drilling project for a driller turned mentor is an ego. Getting upset or creating blame does not help overcome. Project failures require team discussion and smart planning to get back on track. At the moment of failure, all team members have to trust one another and feel safe calling for help to troubleshoot when issues arise. When projects wrap up, create an after-action review that seeks out the root causes of any problems. Consider asking teams the following:

- What was expected to happen?

- What really happened?

- Why did it happen?

- How do we prevent it from happening again?

An after-action review gives everyone within the company a better opportunity to understand what happens in the field and the chance to contribute to creating a better way. Drill teams and management must trust one another to be successful.

Creating Teachable Lessons

Great drillers agree that all project experience, whether good or bad, creates teachable lessons. How we distribute these lessons determines the outcome of the next project. These lessons give our people the ability to make good choices, increasing the possibility of successful completion. Great drillers have a responsibility to prevent new drillers from experiencing the same failures they did. Drillers who do not believe that philosophy will not be our best candidates for coaches, and will likely change assistants every four months.

Click here for more business tips!

We are developing millennials and generation Z employees into 21st-century drillers. These men and women will be challenged to provide water for nearly 10 billion people by 2050. As an industry, we must put more focus on creating a driller-development culture that goes beyond family and neighbors if we expect to have enough great drillers and mentors to fight the global water crisis.

Looking for a reprint of this article?

From high-res PDFs to custom plaques, order your copy today!